This D’var Torah was given at the final Shabbat service of my first year of rabbinical school at Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion, Jerusalem campus, May 2014.

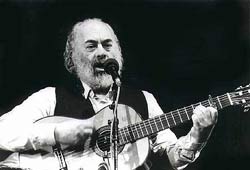

Shiru l’adonai shir hadash. These words of the ancient Psalmist are some of the most beloved today, especially because of Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach’s beautiful rendition that is now sung worldwide during Kabbalat Shabbat. We all know Rabbi Carlebach from his renowned rejuvenation of Jewish music, but we tend to forget his other accomplishment of helping to bring Chasidic thought into mainstream Judaism. The power of the transformation he affected in our own movement is so clear that his own daughter Neshama recently declared her “aliyah” to Reform Judaism. His ability to radicalize Jewish mystical thought is well attested. Some may even say that he went too far at times.

Once, before leading a community in his rendition of Psalm 96, he asked, “How could it be that with all the Torah that was being studied and all the great luminaries in Europe, this tragic event could have occurred?”

We tend to shy away from answering this question when it comes to the Holocaust, or really any tragedy that has stricken the Jewish people in Modern times. Rabbi Carlebach was not so shy. “Perhaps,” he said, “The Torah being studied there was not good enough. Perhaps we need a new Torah.”

Shiru l’adonai shir hadash.

In our Torah portion this week, B’hukotai, we are regaled with a whole host of blessings and curses based on whether or not the Israelites follow God’s laws. Of course, one must immediately ask which laws. Reliable as always, Rashi jumps right in stating that what the Israelites, and therefore we, are commanded to do is toil in the study of Torah. This study is described by Rashi to be the foundation for maintaining the covenant with God, as he states that one who does not toil over the Torah, will then not fulfill the commandments, which leads to despising those who do follow the commandments and hating the Sages, which itself will lead to preventing others from fulfilling the commandments, and eventually ends with denying the authenticity of the commandments and God as well.

If there’s one thing I really don’t like, it’s a slippery slope argument. Yeah, I know, mitzvah goreret mitzvah, aveirah goreret aveirah, but I’d rather flip Rashi on his head here and declare these things in the positive. To keep the covenant we must toil over Torah, which will lead us to following the commandments, loving those others who also do, and our Sages, and so on and so on, until through our embracing of our tradition we finally see, understand, and accept the omnipotence of God.

By flipping this around, we end up with a totally different relationship to God and the commandments. Our first step, which we have all embarked upon in earnest this year, is toiling over the Torah. We’ve toiled over the Torah of Moses, the Torah of Hazal, the individual Torah of each individual’s personal experience, and the wonderful Torah brought to us by all of our faculty. Sounds like we’re on our way to some blessings, right? The rest of the path will just flow naturally out of our learning. And, following this, one of the blessings our Torah portion says we will receive for doing as God commands is that God will set up a covenant with us, with God’s people. In Rashi’s interpretation of this blessing, he sees the promise of a new covenant with the Israelites once they settle in their land, studying the Torah that had yet to be fully written.

Funny enough, in the narrative of the Torah, we’re just now ending Leviticus, which means the first covenant has only just now been established. In conjunction with this fact, the Israelites still have two books worth left of trekking before they reach the destination in which this whole blessing and curse formula will take effect. They are still a full generation out of their Promised Land, and are already being dealt out the stipulations for their descendent’s eventual habitation there.

We too are in a similar situation. We’ve just finished the first leg of our journey towards a lifetime of devotion to the Jewish people, and we know that there’s an endpoint to this training somewhere out there, but we may as well have the Sinai desert, checkpoints, border crossings, and all, between us and the endpoints of our programs.

We’ve also received quite a few warnings of blessings and curses that may come during the rest of our long haul in regards to our levels of toiling. Sure, we haven’t been threatened with having our sky turned to iron and our ground to copper like God threatened the Israelites, but I’ve got a feeling that our administration has some serious smiting power. So we’d better be toiling over that Torah. The question, though, is which Torah?

Rabbi Carlebach’s question about the Holocaust, and suggestion as to the answer, is rooted in a Kabbalistic teaching about the nature of Torah. According to the mystics, the Torah is to be renewed in every generation. It is remade by the masters for the students in a way that meets the needs of the particular time and place. One reading of his statement about the Torah of Europe prior to the Holocaust is that to make way for a new Torah, the old one had to be destroyed.

If we apply this idea to Rashi’s reading of the new covenant that was to be established should the Israelites follow all of God’s laws, what does this mean about the old covenant? Should we, as Reform Jews, be reimagining our covenant with God not only in terms of continuity with the past, but also to supersede the past? The first Reformers certainly did when they made their big break with the orthodoxies of their time, but what are the Reform orthodoxies of our time that make up our generation’s received, but yet to be renewed, Torah? What are we taking for granted?

I think that this question should be at the very core of each and every one of our minds. Ordained or still in school, part of the faculty or administration, if we are truly a community focused on Reform, the verb and the movement, our relationship to the past and the past’s relationship to the future should be weighed in every programmatic, theological, liturgical, and pedagogical decision we make. Shiru l’adonai shir hadash. Sing unto God a new song. We sing this regularly, often without considering the fact that it is a command. Even someone like me who doesn’t know the difference between soprano or tenor is commanded to sing a new song, in spite of the distress it might cause to everyone else’s ears.

Rashi, although obliquely, said the same thing: Toil over the Torah until a new covenant is made. Rabbi Carlebach said it much more directly: Sometimes the old Torah must make way for the new. Both of these men were ardently traditional, but both saw a path forward not through more of the same, but through the new.

This year in Israel I have been very lucky to be exposed to some wonderful new phenomena arising throughout the country. An attempt to renew the Israeli population’s relationship to Torah is under way. Dr. Ruth Calderon and those like her pushing for a renewal of the relationship of the hilonim to our textual traditions have made great strides. Yossi Klein Halevi sees hope in this renewal through the Israeli music scene, which we were lucky enough to experience first hand with Kobi Oz, System Ali, the rejuvenation of modern piyyutim, and countless other musical expressions of Judaism in Israel’s ever-growing music scene. I heard that some Israelis have even begun calling the people ordained here at HUC rabbis! The battle towards a new view on Progressive Judaism in Israel is underway, even if it sometimes seems bleak. The new Torah of the state of Israel is already being written, some of it right in these hallways.

Rabbi Carlebach’s reading of the Holocaust and its relationship to Jewish history and religion is definitely a radical one. There are many who would protest any such use of the Holocaust within a theological or religious framework due to the extremity and closeness of the event. These individuals would have a strong argument to do so. Regardless of the legitimacy of his thought, he made the statement. He taught new Torah from his heart.

Let us embarking upon a path of Jewish leadership not forget that we too can do this. We too can sing a new song, teach a new Torah. And not only can we, but we must. B’hukotai demands this of us, and so does the world. Let us teach a Torah of inclusion; a Torah of fearlessness in the face of change; a Torah no longer striving to maintain Jewish existence only for its own sake, but striving to make the Jewish people a blessing to all of the nations of the world; a Torah focused on how to bless our lives with meaning, not on a constant looming fear of curses. Wherever there is life, there is new Torah to be learned, and then to be taught. Let us never settle for teaching the same Torah that has been taught before. Let us teach a new Torah, each and every one, for the good of the Jewish people, and the good of the world. Shiru l’adonai shir hadash. Shabbat Shalom

Hello webmaster do you need unlimited articles for your page ?

What if you could copy post from other blogs, make it unique and publish

on your blog – i know the right tool for you, just type in google:

kisamtai’s article tool